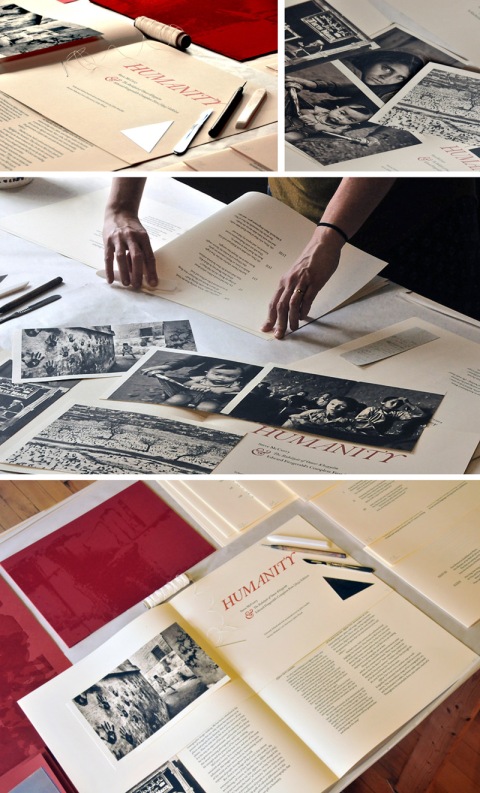

Humanity – In Production

June 9, 2016 § Leave a comment

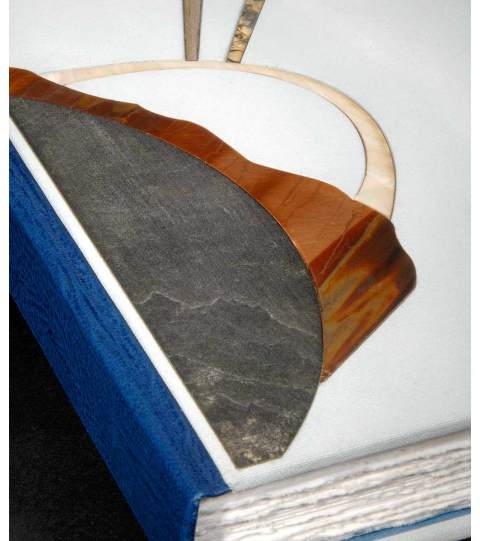

While driven by a passion for The Art of the Book, each of our titles in the soon to be complete 21st Editions Master Collection takes diligence, patience and intense focus. Humanity, our 57th collaboration involving 10 artisans, is no exception.

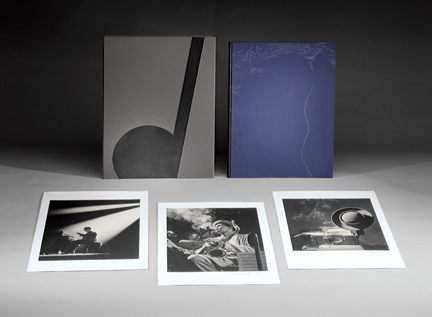

Here is what is involved in the making of Humanity: Conceptualizing and developing the content; designing the book; contact printing the platinum prints one at a time; selecting the paper; making or preparing the text paper to size; making and printing the letterpress plates; folding each signature to prepare for sewing; silk-screening the fabric for the box covers; cutting the separate pieces that will make up the box; constructing and lining the box; designing, printing, trimming and attaching the paste and flyleaf papers for each book; preparing the cloth for adhering to the cover boards and stamping them; trimming and tipping in nine platinum prints; making the folder for the three free-standing, signed platinum prints; attaching the finished cover boards to the sewn book block; marrying all fifty sets; and finally numbering each book before shipping to institutions and collectors at the end of the year.

Please call Pam or Steven (508 398 3000) regarding copies of Humanity that may still be available.

HUMANITY & The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

March 22, 2016 § Leave a comment

McCurry’s work presented in platinum for the first time.

Although Steve McCurry is best known as a color photographer, we have printed these images in platinum. There are two reasons for doing this. The first is to highlight the degree to which McCurry’s work needs to be appreciated not only in the tradition of documentary, but also as a fine-art photographer. Critics typically refer to him as a documentarian. And yet the subtle tonal ranges and luminescence of these prints, coupled with the artistry of their compositions, reveals that they are at least as much “pictorial” as documentary. They explode the lingering and largely false dichotomy between fine-art and documentary photography.

…these platinum prints showcase new forms of McCurry’s humanity, as compelling as their color counterparts. One might say that in different ways, each format highlights connections: between photographer, subject, and viewer; and/or among the people in the images. In both formats, it is as though McCurry penetrates beneath the surface into the heart and spirit, giving us a unique intimacy with his subjects. In doing so, he enlists his subjects as evangelists as few artists have done, bringing people together from around the world.

– from the introduction by John Stauffer

Announcing: Steve McCurry’s HUMANITY

February 11, 2016 § Leave a comment

Twelve signed platinum prints, of which three are loose, illustrating Edward Fitzgerald’s complete first (1859) edition of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. This is the first time that Steve McCurry’s work has been presented in platinum.

“Steve McCurry is one of the best-known artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and one of the most influential. His images have helped connect us to parts of the world we have never been to, humanizing our perceptions of people throughout the world.

But there is one image of McCurry’s that almost everyone knows, even if they don’t know who made it. We are referring, of course, to Sharbat Gula, Afghan Girl (1984). It is not too much to say that Afghan Girl has changed the world, “searing the heart” of viewers, owing to its power to inform our perception of humanity. For over thirty years, it has enabled millions of people to connect with another person across wide gulfs of cultural difference. It is this sense of connectedness, achieved through photography, that is McCurry’s great and rare gift to humanity.”

– from the introduction by John Stauffer

About the Contributors #15

October 1, 2015 § Leave a comment

Over the years John Wood created many unexpected pairings. The resulting titles were interesting new interpretations of contemporary and classic text and photography.

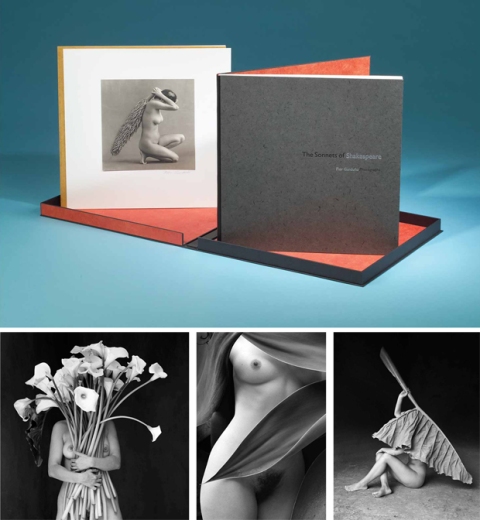

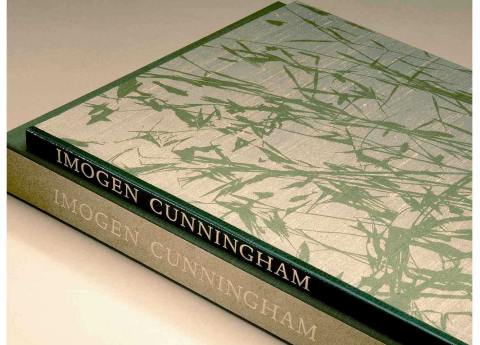

Examples include Flor Garduno illustrating The Sonnets of Shakespeare, Brigitte Carnochan’s flowers and nudes with Raul Peschiera’s The Shining Path, and Imogen Cunningham paired with William Morris.

John Wood, from The Sonnets of Shakespeare

…The reason the sonnets were immediately seen as applicable to a women is because of their universality. They are about Love and its power. An artist’s intention is historically interesting to note, but it is by no means the sole meaning of a work of art. Art always speaks to us in ways its creators did not envision; that is its power; that is why it lasts. And it is only in the context of the narrative of the entire sequence that particular poems, with few exceptions, can be identified as having been written for the young man. No one reads sonnet sequences for their plots, since lyric poems do not really tell stories, and few people read them from start to finish. One picks and chooses and reads randomly for pleasure. And so these universal poems are finally monuments to the universal power of love and the finest such monuments in the English language.

I spoke of Shakespeare as a great psychologist, but so is Flor Garduno. She understands woman more universally, it appears to me, than any other visual artist. She sees woman in all her dimensions-as Siren, Eve, Medusa,Venus-sees her in the sweep of all her varied powers and attractions. Her work is finally a deeply moving tribute to woman, to all women, because, as I suggested earlier, her Venus is Everywoman.

Shakespeare’s genius, like Garduno’s, comes from his deep understanding of human nature. In play after play we see ourselves strutting about in all the cruelty, jealousy, meanness, bad temper, good humor, compassion, honor, and love we are capable of. He shows us our burden and our glory…

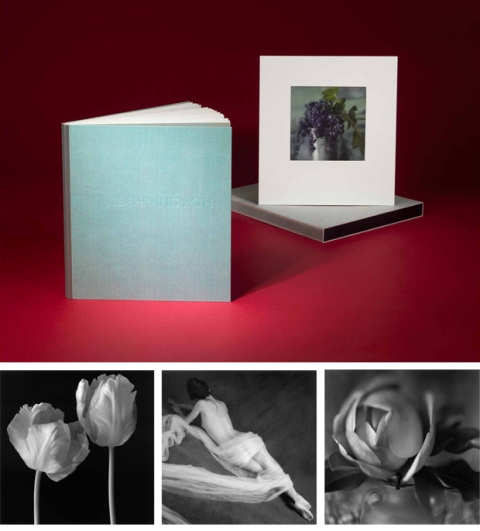

John Wood, from The Shining Path

…That is Carnochan’s shining path-beauty in perfect measure. But that is not The Shining Path of Raul Peschiera’s brilliant poem that accompanies these photographs. The shining path he refers to is Sendero Luminoso, a violent Peruvian revolutionary movement of the 1980’s that disrupted the country’s economy and caused perhaps as many as 25,000 deaths before its leader was captured in 1992.

Carnochan photographs and Peschiera poetry might then seem not merely a strange marriage but an impossible yoking of two dissimilar bodies of work having nothing in common. But a perusal of Peschiera’s poem makes it clear that his shining path and Carnochan’s are the same. He writes of the same intoxication with sensuality and beauty that Carnochan photographs. The central figure of his poem is ostensibly Abimael Guzmán, the leader of Sendero Luminoso, and the poem narrates several of Sendero Luminoso’s most violent acts, but The Shining Path is actually a love poem with both Guzmán’s wife, Augusta, and Peru at its center. In the eye of its turbulent violence slumber luxury, calm, and pleasure. And Peschiera invites us into the dream.

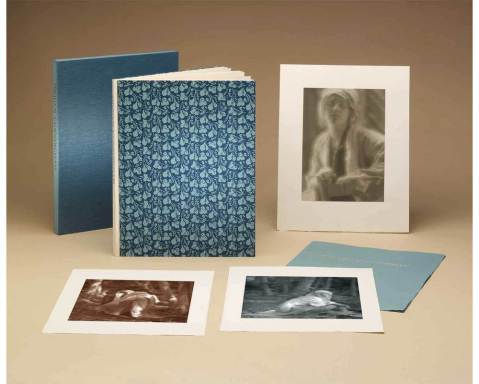

John Wood, from Symbolist

What influence, one might wonder, could William Morris, poet, Utopian Socialist, revolutionary, English Arts and Crafts movement leader, textile and furniture designer, Pre-Raphaelite, a founder of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, and creator of the Kelmscott Press, have had on the work of the great Modernist American photographer Imogen Cunningham? Hardly any, one might assume. Yet she claimed him as an influence, and his influence was intellectual, social, and visual.

Cunningham, a radical herself, grew up in a radical and progressive household, and so her sensibilities were ripe for the influence of William Morris. Her father was “a humanist” she said. “There’s no question about that. And his…life was much motivated by theosophical beliefs. He never drove it into anybody, or tried to tell people what they ought to think,….”

About the Contributors #14

October 1, 2015 § Leave a comment

JOHN WOOD

Not only was John Wood our editor for more than 15 years, he is a brilliant and established poet

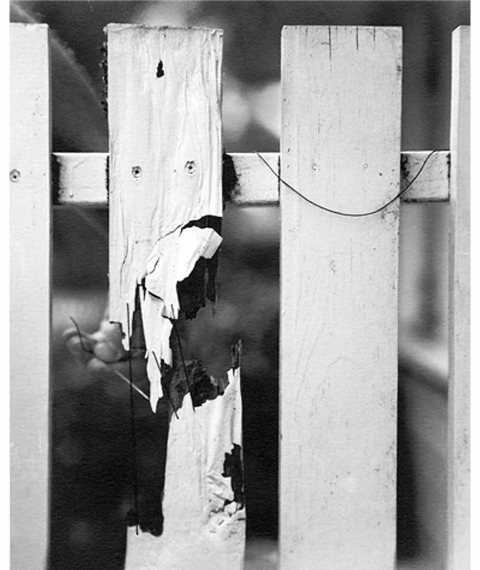

from Cracked: The Art of Charles Grogg

Though I am a photographic historian and critic, I am primarily a poet; however, except for writing a few Japanese waka in homage to my friend Masao Yamamoto, I have never written poems inspired by the work of any of the photographers whose work I have written essays about. The photographs, though wonderful, never suggested subjects to me-until I encountered Charles Grogg’s work. It would be improper of me to write about the poetic aspects of my own work, but I can say something about their content as it refers to Grogg’s art.

The fence-mender of the poem “Fence” is, of course, Grogg, and fence-mending is a metaphor for his art making. The poem makes clear that it is his “chosen profession” but also makes clear that he has not chosen it but that it chose him and that his re-shaping, re-forming art is to my eye a profound expression and act of love…

FENCE

The fence mender’s dilemma is

how to proceed. There’s always

such hostility on either side.

Being in between contorted faces

is distracting, as is avoiding

the flying spittle, the occasional stone.

Rain coats and shields are useful,

especially when he becomes the target,

which is more often than not.

But who would give up a chosen profession?

And for what: becoming a snail driver,

a semaphore man, a town crier,

a berry buster? Certainly not for one

whose profession had chosen him.

There is no choice in spite of rocks and spit,

the cumbersome garb he must wear. And so

he continues buying the costliest needles,

gold-tipped, of course, and iron-strong thread

spun from the silk of golden orb weavers.

His hands dance along the sad shatters

with the confidence of a cosmetic surgeon

re-forming the destines of the unloved and ugly.

Such mending mastery as his is love’s

most profound, best, and final act.

from The Symmetry of Endeavor

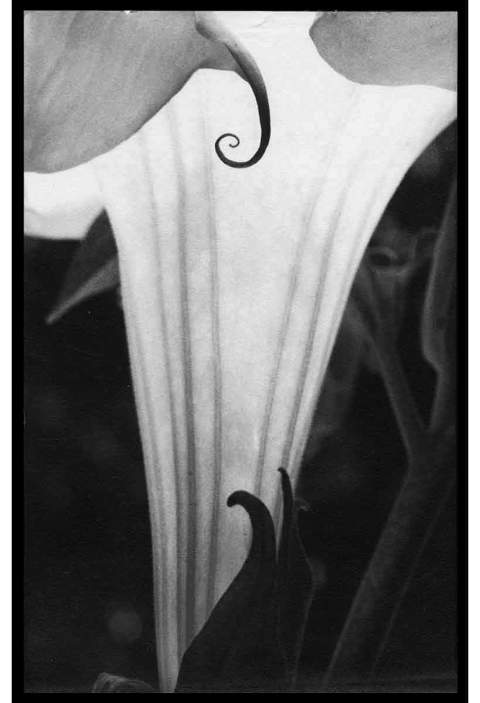

When we look at images as radiant as his wide Calla 3, his tall lean Calla on Black, his Sunflower Rising, which looks like the sun itself aflame, the Nile Lily Bud or his Melinthus in the Rain, as perfect a wet leaf as I have ever seen in any photograph, we see exactly how a master artist manipulates craft to the higher service of his art, how he makes craft the vehicle and servant of his art. His Luminescent Datura seduced me from the first moment I saw it. Besides being a beautiful flower datura, of course, is also a powerful drug, a sexual stimulant, and has been associated with women called witches since the Middle Ages. However, without thinking of any of those things, when I first saw this amazing image, I did not see the flower at all. I saw a lady with a slim neck in an Art Deco gown, her face cropped from the photograph, a curl from her head falling on her shoulder, her right arm bent at the elbow and resting on a piece of furniture, obviously by Ruhlmann, and her hand, though out of sight, holding either a martini or a cigarette. I saw Paris in the Twenties when I would have loved to live there. Such imaginative leaps are the leaps that art graciously allowsand which inspired the poem that follows, even thoughI am certain my lady or thoughts of Mistinguett, the great chanteuse of that time, or the famous club Le Boeuf sur le Toit was nowhere in Rondal Partridge’s mind when he made this work. His thoughts were on capturing a flower. My thoughts were on sex. But great art always transcends the intentions of the artist. That is its blessing and occasionally the artist’s curse.

LADY IN A FLORAL DRESS

A curl cascades, reclines upon her neck.

She stands against a lacquered cabinet.

One hidden hand holds her drink,

the other, a Turkish cigarette.

This Deco dame is surely French

and probably knows Mistinguett.

Would she accept a little pinch,

then smile and say with no regret,

“Was it Le Boeuf sur le Toit where we met?

We danced. You held me in a clench

and called me mon petit pet.

Men like you I never forget.”

He wondered what could be her game.

His, of course, was exactly the same.

from The Imponderable Heart of Meaning

As we approached our sixteenth year of publication, Steve had the happy idea of our doing a book together-his photographs and poems of mine inspired by them. Though I have been writing poetry for over half a century, I cannot say I know where poetry comes from, but I know it is very hard to make a poem from a work of visual art. I said I’d try and with a great box of Steve’s prints before me, I was surprised to see how words quickly started to appear and shape themselves into lines and eventually poems. In every case it was his visual magic that inspired the poem. So these poems are a real monument to our years of friendship and work together.

I had hoped that this volume would be entitled In the Face of the Electron because that is the title of a poem I wrote for one of Steve’s most amazing and brilliant photographs-an abstract image of the most intense power, an image that allowed me to look into the face or heart of the electron… I’d hoped we would use the photograph because I love it but also because of the poem it led me to. My own work, though sometimes comic, tends to be dark, somber, occasionally even savage. But what Steve’s photograph allowed me see was something rich and affirmative…

IN THE FACE OF THE ELECTRON

In the unstopping spin and swirl

of matter’s uncertainty, it can

sometimes be caught unaware

and resting for a short fraction

just as the more common birds

are often caught, and so

the Nature artist must be quick

and snap it before it flies off

as the fastest light excels,

to snap it before the electron’s

huge and fluffy wings again

begin to beat, driving matter

mad in its motions, and before

its beak begins again to peck

at the atomic shell, and before

its maddening dance must begin

again to hold everything together,

secured in the electron’s hold,

its wide-wings’ generous, spinning embrace,

succoring with no knowledge of its doing so

the imponderable heart of meaning.

About the Contributors #13

October 1, 2015 § Leave a comment

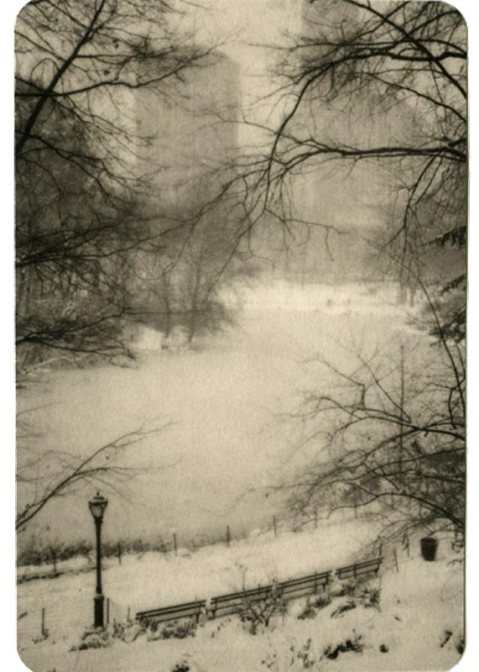

Michael Murray, an unknown, pioneering New York-based artist (originally from the home of Kodak, Rochester, NY) was selling his work at a kiosk on Poet’s Walk in Central Park when he was discovered by Gideon Bosker who then presented his work to 21st Editions.

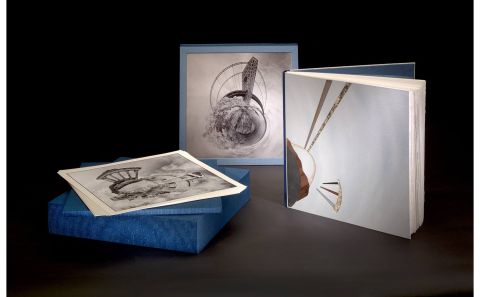

In Worlds Apart, Gideon introduces us to Michael Murray’s presentation of the world, John Stauffer tells us more on the myriad places where he created his images, and John Wood completes the story with an eloquent poem.

GIDEON BOSKER from Worlds Apart

Long before I knew Michael Murray had photography wriggling in the helices of his DNA, or that as a young boy he spent family day each year feasting on Nathan’s Famous hot dogs with his father in the Eastman Kodak commissary on Lake Road in Rochester, New York; or that the dreamlike, elliptical beauty of such films as Thin Red Line by Terrance Mallick “changed everything” for him; or that the murky interface of quantum physics and spirituality is consistently in his mind’s eye as he conceives, pre-visualizes, and manufactures his photographs-long before I knew these and all the other things about Mr. Murray and his iconoclastic life, I knew the first time I glimpsed the photographs he was hawking from bins on Poet’s Walk on a frosty, skin blistering November day in Central Park, that the images this photographer had spent years perfecting were digging deep into unchartered territory…

It took only a few minutes of scouring through his images that day in the winter of 2012 for me to conclude that, in his lens, Mr. Murray had the whole wide world…

Under the influence of new technologies, from the first pinhole camera to the razzle-dazzle of digital photography, the camera has always been poised to enrich our engagement with the world. It is on this trajectory, that Murray’s ingenuity stakes its claim. His photographs are testimonials to the power of photography for introducing a new perceptual framework: one based on the melding of technology with the camera arts for the purpose of remaking the world so we might engage it; and so it might stir us and so we might dream about it in new ways.

Aside from the sheer density of information these photographs extract from a single coordinate of longitude and latitude, there is a seething undercurrent of spirituality in Murray’s work: a dimension-call it a portal to another world-that provokes what can only be described as reverential impulses. Perhaps, this is not surprising, since geometric configurations linked to centralized space have deep religious roots and have been used for evocative effect for centuries…

JOHN STAUFFER from Worlds Apart

Cathedral Gorge, a state park in Nevada, is in Lincoln County, about 160 miles northeast of Las Vegas. Standing a little less than mile above sea level, it looks primordial.

The gorge was created millions of years ago, when volcanoes erupted and deposited massive walls of ash. During the Pliocene epoch (5.3 to 2.6 million years ago), a freshwater lake filled the gorge. By the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 12,000 years ago) the lake had drained. The continual erosion of the soft volcanic ash made plant life difficult but created beautiful patterns on the walls of the gorge that resemble tessellations. Since it was not good farmland, scientists in the mid-nineteenth century began referring to it as “badlands.” Yet for hundreds of years it was also the home of the Fremont, Anasazi, and Southern Paiute tribes. Bison bones were recently discovered in the gorge that are between 400 and 850 years old.

In Murray’s dramatic rendering, turbulent chiaroscuro clouds surround the desolate gorge. There is no sign of plant or animal life. And yet the rocks themselves seem alive. The tessellating cliffs seem like gates of an elaborate kingdom, breathing hymns of the gorge’s history.

Wallace Stevens provides a poetic echo of Murray’s gorge in “Forms of the Rock in a Night-Hymn”:

The rock is the gray particular of man’s life,

The stone from which he rises, up-and-ho,

The step to the bleaker depths of his descents . . .

The rock is the stern particular of the air,

The mirror of the planets, one by one,

But through man’s eye, their silent rhapsodist.

Through Murray’s eye, we see Cathedral Gorge as a silent rhapsodist.

JOHN WOOD Bruegelesque:

A Seasonal Meditation on the Grace of Michael Murray’s Eye

Small black shafts rise

in the surrounding snows

and lean back into the past,

into forgotten dancing days

hard on the ice of ponds

swirling with skaters

in the cold afternoons

of painted near memories.

Smoke rises from the red house

beside the swirling shallows

of the river. There is no sound

but the quiet of silent cold.

Winter will still last longer.

Nothing is yet finished

until the bounding crocus agree

to arise into his eyes.

About the Contributors #12

October 1, 2015 § Leave a comment

The beginning of this year brought a new Editor to 21st Editions, John Stauffer. John’s credentials are numerous (a tenured Harvard Professor with 15 books, more than 100 articles, scholarly awards, and much more). He continues to offer a rich historical context for the photographs and artists represented in many 21st Editions titles.

JOHN STAUFFER ON

Todd Webb: New York, 1946

When Todd Webb arrived in New York in November 1945, Henry Luce’s famous prophecy, uttered five years earlier, that the U.S. would become the “leader of the world” and launch an “American century,” seemed to have been realized. The war had made America rich and powerful while decimating much of Europe, and artists flocked to its cultural center. There was now talk that New York might replace Paris as the world center of art and culture, as Serge Guilbaut has noted. But “it was important to find the right image for America and its culture,” which would “mirror the experience of [the] age.” This image would need to resonate with the formal and ideological sensibilities of New York and the U.S., as well as the rest of the art world. In painting, abstract expressionism would become that image. Jackson Pollock’s seemingly random drips of paint evoked an existential angst that mirrored the “experience of the age.”

In photography, the idea and image of the city became the symbol of the new postwar world. In 1946 alone, Webb shared the streets of New York with Helen Levitt (with whom he sometimes photographed), Berenice Abbott, André Kertész, Minor White, Gordon Parks, Aaron Siskind, Paul Strand, Andreas Feininger, Weegee, Dan Weiner, and Sid Grossman.6 Unlike his peers, Webb was comparatively new to photography; he called his arrival in New York “the beginning of my career in photography.” Several people, including Paul Strand and Roy Stryker (for whom he eventually worked), advised him to go back home to a “safe” job inDetroit. “How lucky I was to refuse [their] advice.”

How lucky we are as well. Alfred Stieglitz, Webb’s mentor and friend, was right: there is in Webb’s New York photographs a tenderness without sentimentality that set him apart from his peers. As Stieglitz knew, photographers tended to portray New York as hardboiled or ironic or lyrical or messy, but never with tenderness. The word was not then associated with the city. (It rarely is today.)

There is also in Webb’s New York a sense of regenerative exuberance that stemmed partly from the war. Following the allied victory in Europe and the liberation of millions of prisoners from Hitler’s fallen Reich, people throughout the West began to hope for a unified world (“One World”) devoted to peace, freedom, and harmony among nations. But the exuberance did not last. Visions of “One World” vanished after Hiroshima, the rise of Soviet aggression, and the specter of a third world war. As a result, 1945 ended on “a mixed note of gratitude and anxiety,” as Ian Buruma notes. People had “fewer illusions about a glorious future and growing fears about an increasingly divided world.” They wanted above all to get on with their own lives. “During a worldwide war, everywhere matters. In times of peace, people look to home.” Todd Webb’s New York is a symbol of America’s home in the wake of war, in which people have retained their faith “One World.”

JOHN STAUFFER ON WOMEN IN PHOTOGRAPHY

Imogen Cunningham: Family

Cunningham knew that women faced formidable social and economic barriers…but she also recognized that as a profession, photography was comparatively open to women. Not only was there the force of Käsebier, but Jessie Tarbox Beals and Frances Benjamin Johnston were prominent photojournalists, and the San Francisco Pictorialist Annie Brigman had recently been published in Camera Work. Indeed women had played important roles in photography from its inception. Constance Fox Talbot, Henry’s wife, was one of the very first photographers; Nancy Hawes hand-tinted Southworth and Hawes’ daguerreotypes; and Julia Margaret Cameron was among the nineteenth-century’s most accomplished portraitists. Before the Civil War there were thirty-nine professional women photographers on the west-coast alone. “Photography is the democratic art,” Cunningham said in her manifesto, because it depicted “the life of the masses” and accepted women.

Photography’s comparative openness toward women was due to several factors. There were few barriers to entry; start-up expenses were modest; and the profession required no formal apprenticeship in which masters could exclude women. Then too, photography did not suffer from the myths of genre superiority that plagued painting and sculpture, whose cultural gatekeepers excluded women from exhibitions and museums.

The main argument of Cunningham’s manifesto, however, was that “women as well as men need to be granted the right of self-expression through work.” Women, like men, wanted fulfilling, creative professions without having to sacrifice marriage and “the care and rearing of children.” Cunningham no doubt imagined herself eventually marrying and having children while remaining devoted to her profession. Photography was in this sense an ideal profession, and it could have “an enlarging effect upon the home.” Why? Because “being devoted to one’s work is much like hearing a great Wagnerian opera with one’s soul open. The energy and vitality of life seems for a time sapped but comes back in renewed quantity and quality.”

…It was as if Cunningham’s manifesto/artist statement prepared her for what was soon to come. Two years after publishing it, she married Roi Partridge, an accomplished etcher. Ten months later, in December 1915, she gave birth to their first child, Gryffyd, followed by twins, Rondal and Padraic, in 1917. Partridge did not share her New Woman values; he taught art at Mills College while also creating his own art, and rarely contributed to childcare. And so for the next decade and more, Cunningham heroically juggled career and motherhood by focusing on subjects at home: her children and the plants in her garden. In this she became a model for subsequent generations of female photographers (one thinks especially of Sally Mann’s Immediate Family).

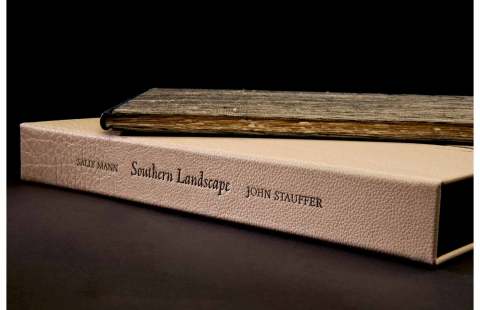

JOHN STAUFFER ON SALLY MANN’S

Southern Landscape

Mann’s photographs, especially her landscapes, are also intimately connected to her Southern identity. In her Massey lectures she emphasized that we cannot understand her art without acknowledging her Southerness. “Maybe nothing so engages the Southern heart as a good piece of family land,” she said, referring to herself. Born and bred in Lexington, Virginia, she lives with her husband Larry on a farm partly inherited from her father, and she has said that she will be buried there as well. Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are also buried in Lexington. Mann was born in Jackson’s home, and one of her early photographic projects was to restore, print, and file glass negatives of Michael Miley, who is known as “General Lee’s photographer.” Lee and Jackson are of course the twin gods of Southern memory, a kind of Father-Son duo. Their “last meeting” before Jackson was killed at Chancellorsville, with Lee astride “Traveller” and Jackson on “Little Sorrel,” is an iconic image, among the most popular Southern historical prints. You might say, then, that Lexington, Sally Mann’s home, is the Jerusalem of the South.

Perhaps it is no wonder that Sally Mann is drawn, both in her images and the literature she reads, to the gothic, with its eccentrics, its haunting, and its unruly landscapes. “I think the South depends on its eccentrics,” she has said, and she considers herself one of them. Her work undermines prevailing platitudes, from perceptions of children to the South’s “Lost Cause,” which ignores the horrors of slavery and Jim-Crow segregation and presents the Old South as a utopian paradise. She named her son Emmett, in part after the young Emmett Till, whose lynching in 1955 sent shock waves throughout the country, exposing the savagery of Southern segregation; and she photographed the spot where Till’s body had been dumped into the Tallahatchie River. She aptly revised Flannery O’Connor’s understanding of the South as “Christ-haunted”: “I say it’s death-haunted.” It is haunted by (among other things) the deaths of slaves, the deaths of its white men during the Civil War, and the deaths of lynching victims during Jim-Crow segregation. And she is explicit in connecting her photographs of the Southern landscape to the South’s haunted past: “The pictures I took on those awestruck, heartbreaking trips down south were pegged to the familiar corner posts of my conscious being: memory, loss, time, and love”…

About the Contributors #11

October 1, 2015 § Leave a comment

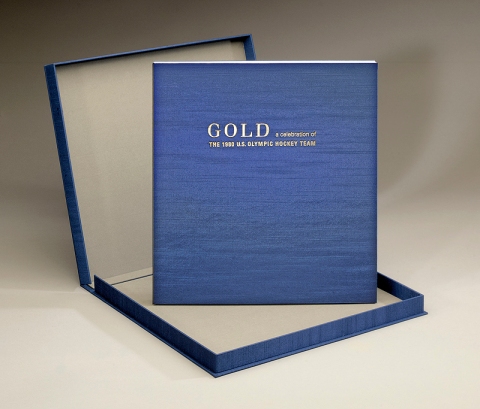

Legacy Editions and and legacies in music. Quincy Jones writes about his longtime respect and friendship with Herman Leonard. Legacy Editions title Love, Graham Nash includes not only text by Graham Nash but has an introduction by the iconic Neil Young. Legacy Editions includes other important cultural icons, Al Michaels and President Jimmy Carter in Gold, not to mention text and signatures from the entire team!

Two Jazz Legacies, Quincy Jones and Herman Leonard

Listen: Herman Leonard and His World of Jazz

Today people talk a lot about “reading” a photograph. That means “getting it,” understanding what it’s all about. But, man, when it comes to Herman Leonard, I think a better verb is listen. You need to “listen” to Herman’s pictures. They are full of music and you can hear it. Just look at his great picture of Lady Day {shown below}. If you can’t hear her singing to that little angel over her left shoulder, then you’re just not listening. Herman’s pictures always swing-and always have some special touch, like that angel, that leaves you wondering where it came from. Look at The Duke seated at his piano. It’s Ellington, for sure, but notice how Herman caught him in those modernistic and elegant shafts of black and white light, which echo Ellington’s elegant, always new music.

I’ve often called Herman’s photographs “perfect.” But his perfection was no accident, no piece of good luck. He did have the good luck, or the smarts, to be in a lot of the right places at the right time. But he learned his craft, the notes and scales of his art, just like we musicians did. Before you can go off on a riff, you’ve got to know where the notes are, and Herman learned all his camera’s notes. He realized at a young age the value of studying with a master and apprenticed with Yousuf Karsh, who wrote that Herman had what it took “to be a great photographer.”

Herman and I have known each other since the early Fifties when I was playing with Dizzy Gillespie’s band. Then in Paris in the late Fifties, and right on till today. And he’s always caught that swing, which is why we musicians always wanted Herman to photograph us. He made us look like our music sounded because he had come to his art the same way we came to ours-by finding our own distinct voices. If there’s ever been a musician’s photographer, it’s been Herman Leonard. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again, his photographs are music to my eyes. And most of all, I have been blessed to have him as my brother and friend for so many years.

– QUINCY JONES –

One of two Legacy Editions titles:

Love, Graham Nash

When it comes to writing songs, most songs seem to be about love, but when love and love of man seem threatened, especially by politics and war, then the subject changes. Sometimes it is easy to write a song about war, if young people are killed on a college campus in the USA because they were protesting a war they did not believe in, and were threatened with the possibility of having to go and fight in, then that is an easy thing to write about. It comes naturally and you just let it go. Then the wars that seem to be so wasteful come along, and you may be a lot older now, like Graham and I are, well then it is different. We are grown men with experience in the world. Our ideals have been battered by life, but we still cling to them, even though we have learned that men fight wars because they breathe. That makes it a lot harder. It makes you a preacher, a politician, all the things you may not want your music to be, and you are caught up in the web. Anger, loss, desperation, they all come to you and make you write songs that seem to separate people, and you don’t know whether you have won or lost.

– NEIL YOUNG –

Without the love and support of my mother and father I wouldn’t be here talking to you. My vision for myself would not have come to pass had it not been for their positive attitude towards my passion for rock and roll.

My father first revealed the magic of photography to me when I was 10 years old and I’ve never been the same since. My mother always encouraged me whatever my pursuit, and it’s from her I really gained the confidence to go out into the world with a strong heart. To them both I dedicate this project and I send my unending love.

For much of my life I’ve tried to share my creations with who ever wanted to take the time to be curious. From the first moment of darkroom magic shown to me by my father so long ago, to this present day, I am driven to express myself mainly through photography and music, and I feel extremely lucky to be able to speak my mind this way. I’m proud to be a part of a society that tolerates my point of view.

The conjunction of two energies, love and pain, is represented here

in these pages. There’s a certain charm about the original scribbling

that seems, in my case, to coalesce into song and image. I certainly hope

you enjoy this journey but please remember that these are my loves . . .

these are my pains. . . .

– GRAHAM NASH –

The other Legacy Editions title:

Gold: A Celebration of the 1980 US Olympic Hockey Team

It’s been often chronicled that the collective mood of our nation in early 1980 bordered on a combination of gloom and anxiety. The prime rate hovered near 20 percent. Long lines at gas pumps in the 70s portended another future round of shortages. The Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan and, as ironic as it now plays out, the United States threatened a boycott of the Olympic Summer Games in Moscow (which did happen). More than 300 Americans were rounded up in Iran and held as hostages, a nightly embarrassment on Capitol Hill and at the State Department. In sum, the United States had a form of the collective blahs.

Out of that darkening vortex came a group of relatively unknown young men and a coach whose focus was limited to performing at the highest level possible over a February fortnight in Lake Placid, New York. When it was over-and the 1980 United States Olympic Hockey Team had won the gold medal-it was a sports upset of historic proportions. But as anyone old enough to remember knows, it broke through barriers far apart from the worlds of hockey and athletics. It gave our country a collective emotional lift and it came out of nowhere. Three decades later, people still light up at the memories.

One of the best things about that magical run is that the flashbacks are so disparate. What did it all mean? I think the answer to that is another question-how many ways can you look through a prism? I know a lot of people still view it as a metaphor for “anything is possible.” In an increasingly cynical world, I suppose that’s one legacy. But I prefer to think of it as something somewhat arguable but slightly more tangible-the most joyous sports remembrance of our lifetime.

One of my favorite phrases is “go make a memory.”

Boy, did that group make one!!

– AL MICHAELS –

Looking back, the 1980 “Miracle on Ice” was much more than an Olympic upset, more than the underdogs defeating the favorite in a hockey game. It was that these unknown, working-class American young men had defeated the all powerful, seasoned Soviet professional team who, months earlier, conquered a team of NHL All-Stars in the 1979 Challenge Cup. The upset came at an auspicious time as the decade that preceded that moment in our nation’s history truly had tested the character of our country. To many Americans, that game was not only a physical victory, but an ideological, even spiritual triumph-perhaps even a success as meaningful in its own nuanced way as the Berlin Airlift or the Apollo moon landing.

America has always embodied an ambitious philosophy of succeeding even under the most daunting odds. When the American team skated onto the ice all those years ago, the result seemed to be a foregone conclusion. Showing the kind of grit and determination that is the very essence of being an “American,” those boys showed us, showed the world the meaning of the word “miracle.” In 1980 we were in dire need of something to celebrate, and those young Americans responded. In doing so they lifted the spirits of an entire nation, and it is a moment that holds a special place in my heart.

– PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER –

About the Contributors #10

September 14, 2015 § Leave a comment

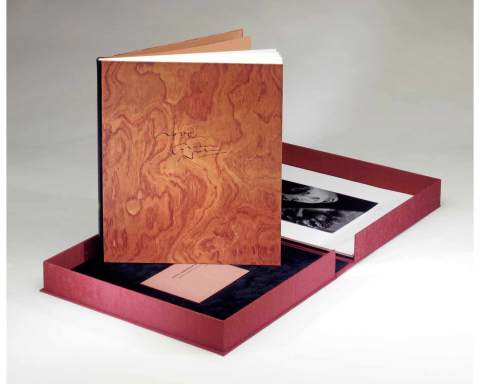

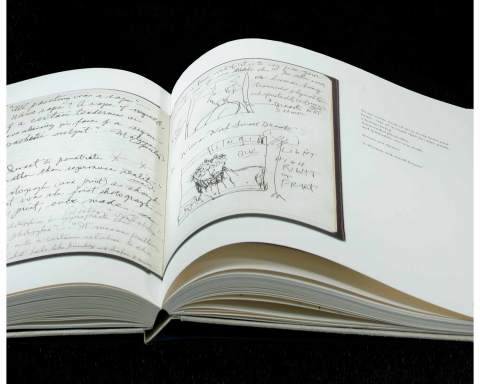

A rare look into personal reflections and thoughts through the pages of artists’ journals, sketchbooks and an interview.

The Maxims of Men Disclose Their Hearts

The Journal of Joel-Peter Witkin

French Saying

“The maxims of men

describe their hearts.”

This is true of art

because the heart (and soul)

must grow in love and compassion.

The artist’s vocation is to purify

his heart & soul in order to develop

a personal vision,

to create

a sacred dimension.

I make photographs because it allows me to proclaim in the Light what I’ve perceived in the Darkness of my being. My faith and my photographs are the reasons I live!! I know I’m not going to change the world with what I make. But I want to make work that the viewer perceives as the reproduction of my Soul. That is my criteria and I believe is the reason all great art is made!

We live in a lost and dying world. A great deal of art produced now reflects this-an art of total emptiness, meaninglessness. This “Art” is a denial of the wisdom of the past presented in the unformed, immature

philosophy of “Post Modern” sound bites.

I want to penetrate rather than reproduce reality. Photograph (and print) as though that was the first photograph or print ever made.

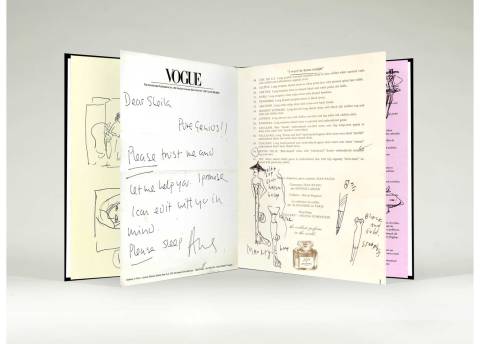

Sheila Metzner: Fashion

M. Fresson,

Thank you for the fine prints. It is as though you read my mind. They are perfect. I would like to continue to work with you in this way for a while. And I would like to continue to experiment…

The “soft-eye” is transforming. One minute you are “looking,” suddenly you are “seeing” everything changes, dimension, sensation of colors, a kind of objective discrimination begins. Thoughts are magnetized to the vision. Like clouds congregate at the horizon. Reality and vision are one. There is no separation. You are to believe in yourself and what you see. Enraptured until the other reality which you do neither inhabit nor own, outright, calls you back.

Imogen Cunningham: Platinum and Palladium

I never photograph ugliness. I am afraid I am a little too aesthetic to be anything but old-fashioned. I agree to that. I let myself be old-fashioned, why shouldn’t I? I have a formula for how to make a good photograph; I think that in order to make a good photograph, you have to be enthusiastic. That is, you have to think about it, like a poet would.

I think everything you do is something of a contribution, unless it’s no good. Then you better hide it. What I like to see about a photograph, is everything smoothly in focus-or if it’s out of focus, for a purpose. And, the quality and gradations of value, rendered, more nearly and accurately in a smaller photograph. I don’t mean tiny, but I mean, not too big. I think still photography has more of an aesthetic appeal, that is the single photograph.

For some people history is a great adventure, for others a great bore. But for me it is overpowering. As far as the history of photography is concerned, I have lived more than half of it. But it still gives me pause.

Jefferson Hayman, the modern-day Coburn

September 4, 2015 § Leave a comment

Jefferson Hayman is the modern-day Alvin Langdon Coburn. Ever since I saw Jeff’s work I knew I was looking at a future entry into the history of photography. After having known Jeff coming up on a decade, I am sure that Jeff’s vision was and is his own. This question begs to be asked because his style is so very akin to the work of Stieglitz, Steichen, and most of all, Coburn. As Coburn may have only enjoyed having an upstage position for about 15 years, I would bet that Hayman is going to be around for the long haul. What he has that is unique to the others is his presentation. That in itself, is as much about his art as is the photograph. Jeff is a conceptualist, a sculptor, and a photographer. All of these reasons are why we published him in “The New City.” If anyone goes to see the upcoming exhibition at the Eastman House (www.eastmanhouse.org) on Coburn, you might want to keep in mind the quiet artist who is making his way in the U.S. and overseas in a deliberate and focused attempt to merely do what he does. The fact that he is doing it very well and that there is no one like him, might give us pause to think what his show will look like when he is long gone. I am certain it will be astounding.

-Steven Albahari

Publisher, 21st Editions